Who Needs a DAM Librarian? Part IV: The Rise of the Information Professional

This special feature was contributed by Deborah Fanslow and is the final item in a series of four articles. A PDF is also available for download.

At last, we’ve reached the point where I can effectively answer David Diamond’s call for information professionals to “come out of the library closet” and tell a story that actually interests employers. Throughout this series, I took a page from David’s book and first set the stage with education, intended to provide sufficient context that would enable readers to more fully understand the implicit value that information professionals can bring to DAM as practiced within the commercial sector. I described:

- Why David and numerous DAM consultants, practitioners, and even a few vendors have increasingly advocated for the recruitment and employment of information professionals in the DAM field, and how a handful of academic institutions are slowly catching on to this demand and adapting their curricula accordingly.

- Who information professionals are, where they come from, how DAM is situated within the family of information professions, and why this context matters.

- How the skills of information professionals stack up against the competencies required for success as a Digital Asset Manager, how these skills are typically acquired, and how new educational opportunities are emerging to help close the gap between industry demands and workforce skills.

As David and others have advised, we should speak the language of our audience, stay benefits-focused, and sell what our audience needs rather than what we know (Diamond, 2014). Now, after providing a foundational understanding of who information professionals are and what skills they bring to the DAM table, I aim to do just that by first describing how information professionals can contribute to the success of DAM initiatives, as David suggested—and then by taking a few steps back from DAM to examine the larger ecosystem in which DAM lives, revealing the additional ROI that information professionals can provide when positioned strategically within an organization’s digital strategy team.

So go ahead and grab your favorite beverage and a comfortable place to read—because this is assuredly where the story gets quite interesting. Let’s check in and see how the second half of our information professional’s interview is going…

Interview with an Info Pro

[Act 1, Scene 2]

Hiring Manager: “If hired, how would you help ensure that our DAM initiative is successful?”

Info Pro: In order to set the stage for a successful DAM initiative, it is wise to study and heed the lessons learned from those in the trenches. So let’s find out where DAM initiatives typically fail, and then explore how information professionals can help prevent these mishaps. If you’ve been with me for this entire journey, you will surely know what’s coming…that’s right—more research.

Back at the start of this series, David Diamond mentioned the most common “DAM Killers:” unclear goals; lack of ownership and decision making; and lack of training, follow up, and ongoing evaluation. Let’s examine the literature and see what other DAM implementation survivors have to say on the subject. First up, seasoned DAM consultants—my favorite source of DAM wisdom:

In a 2008 executive briefing entitled “Why DAM projects fail,” consultants from Three Media Associates acknowledged the inherent complexity in determining the reasons for implementation failures. When considering the technology-vendor-client triad, they maintain that:

“While it is tempting to point the finger at technology, it is usually people related issues that cause a DAM project to fail….Technology should not be discounted; functionality, scalability, flexibility and ease of integration are all factors influenced by the underlying technologies. With that being said, our experience is that the reasons for DAM projects failing usually consists of a combination of reasons attributable to the contracting client and vendor” (p. 4).

A multitude of failure points were detailed, including: lack of integration with business processes, workflows, and other enterprise systems; insufficient requirements gathering; improperly implemented metadata models; lack of user involvement; and change management (p. 5-17).

Two years later, consultant Joel Warwick maintained that “good DAMs go bad” due to insufficient operational design along with a lack of communication, standards, policies, change management, and ongoing services. Warwick identified the underlying issue as a lack of accountability for ensuring that business processes are operationalized successfully within the DAM system. Warwick (2010) stated,

“Implementing DAM involves much more than implementing a DAM system….“The system may function beautifully, but if people use it the wrong way, it will appear not to function properly, such as the inability to find useful content, the inability to use what is found and perceptions of the system requiring more work to use rather than saving time….Issues such as capturing the wrong content, poor tagging, absent rights, unclear policies, mismatched standards and so on are all experienced as ‘I can ’t find it or I can ’t use it ’ (p. 223).

Skipping ahead another two years, Elizabeth Keathley’s synopsis of the inaugural DAM Foundation Salary Survey situated this issue within the context of DAM staffing:

“When digital asset management systems (DAMs) fail, they often do so due to inadequate or misaligned staffing….When a company launches a DAM with little or no dedicated staff to attend to user needs, it has set itself up for failure, no matter the particular DAM vendor or access platform that is used.…In order for a DAM to succeed, a full-time manager must be in charge of the system. Regardless of whether it is a cloud or in-house installation, regardless of the type of DAM, regardless of what the salesperson tells you—there must be a full-time manager behind the scenes in order for a DAM to work” (2013, para. 1).

Looking ahead yet another two years, Mark Davey (2014) also emphasized the need for adequate DAM staffing. According to Davey, DAM implementations require a team of professionals, including a dedicated DAM Champion and a librarian—which Davey suggested is ideally one and the same person:

“The DAM Champion and your librarian (information architect/artiste) are critical in structuring your data for the organization…It’s a mistake to select a system and then hire someone to manage it. You need someone from day one, someone skilled in outreach and advocacy who can walk the workflow with your end users, analyse what kind of access is needed and by whom, and how your people need to work with assets….Ideally your Champion will also have the skills to arrange and describe your assets, provide reference services, maintain access, select, appraise and acquire assets – all skills that librarians experienced in working with large data sets excel in. Despite what some vendors may claim, assets don’t arrange themselves, taxonomies don’t magically appear and create order out of chaos and DAM solutions don’t run themselves. People with the relevant skill sets are integral; you may not be able to afford your dream solution but as long as you have the right people in place, whichever solution you end up with has a good chance of surviving and being deployed effectively and efficiently” (para. 8-10).

Counting over 200 DAM implementation notches in his belt, Canto consultant Benedict Marck identified failure points early on in the implementation process. In a recent interview, he stated:

“I can’t stress enough how important the definition and planning phase is….Like in almost every project the most common and probably the worst mistake you can do is to start without a proper definition of what you want to achieve….As for the completion it is vital not just to deliver the technical setup but to make sure that the DAM supports everyone’s needs in the best possible way” (2015, para. 9-10)

It should not go unnoticed that the limits of DAM system technology were not mentioned at all by these consultants as a factor in the failure of DAM implementations. Rather, proper staffing, sufficient planning, proper information management/governance, and people issues were the main failure points identified. Now, let’s take a look at what DAM analysts, the folks whose businesses revolve around evaluating DAM technology against a broad range of use cases, have to say about the matter:

In a 2012 article advocating for the use of the DAM Maturity Model, Real Story Group analyst Apoorv Durga stated:

“Projects continue to fail, even though IT technologies and processes are much more mature now than they were only a few years ago…. [reasons for failure] include: absence of a solid business case that justifies a DAM implementation; wrong product/tool selection; not allocating enough budget; business processes not addressed; lack of user training and education; lack of top management commitment and sponsorship; lack of stakeholder participation. It is often found that users assume technology will solve all their problems. But as can be seen from the indicative list above, tool selection is just one of [the] considerations” (p. 183).

A year later, Forrester analyst Anjali Yakkundi shared highlights of Forrester’s research which revealed the key determinants for successful implementations as reported by organizations that had lived through a DAM implementation and come out the other side successfully. Choosing the right vendor and product was one of the factors listed for success, but just as critical were the other two points—having a flexible implementation plan based on business needs and self-service, and recognizing the importance of governance and change management. In her summary, Yakkundi (2013) listed the familiar issues of deficient information/workflow analysis, misaligned data structure, and inadequate governance, stating:

“Something that’s very important, but which many organizations overlook, is metadata and taxonomy strategy. Rich media is different than text-based content, so full-text search isn’t going to suffice here….Organizations with successful DAM implementations have built plans to facilitate user adoption including frameworks around both change management and governance. DAM governance, for example, should define processes and procedures for creating, managing, and updating content within the repository” (para. 2-4).

Finally, speaking at last year’s Henry Stewart DAM NY conference, Theresa Regli, Principal Analyst at the Real Story Group, emphasized that failure to dedicate adequate resources to DAM implementations is the main problem these days—not the capabilities of DAM technology.

The aim of this exercise is not to say that aligning DAM technology and vendor capabilities with business needs is not an important factor in the success of DAM implementations. Rather, the point is to emphasize that both DAM consultants and analysts (professionals who are familiar with a broad range of DAM systems) concur with the fact that as DAM technology has matured, system functionality has become less of an issue, and that more often, the culprits of failed DAM initiatives are the “people” and “information” elements, which typically receive less consideration throughout the implementation process. Even from just this small sample of sentiments, one can see that DAM initiatives typically fail most often these days as a result of inadequate dedication of resources (time, staff, budget, etc.) to the objectives and processes within the stages before and after the actual DAM technology is deployed.

Single points of failure—if only there were just one

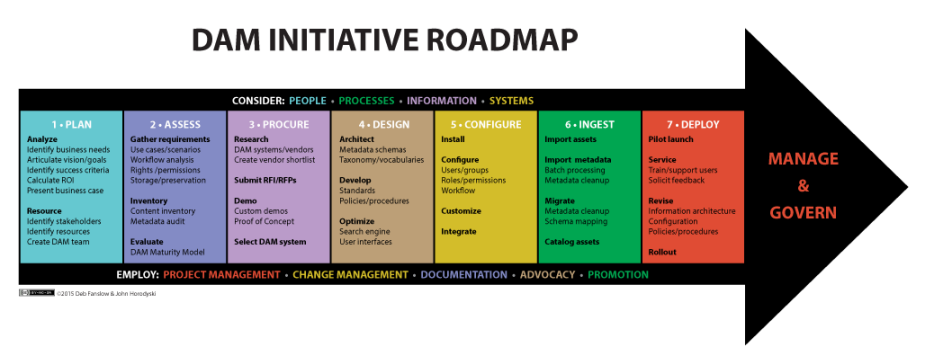

To visualize the failure points mentioned above in context, let’s take a look at the typical process of procuring and implementing a DAM system, and then pinpoint where the missteps described above materialize along the way. Figure 1 below illustrates the various stages of a typical DAM initiative:

Figure 1: DAM Initiative Roadmap – Download PDF

In the above model, the core activities involved in procuring and implementing a DAM system are presented chronologically, flanked by elements and processes that require attention throughout the

entire initiative. The arrowhead symbolizes the management and governance that is so critical for success after a DAM system is up and running.

- PLAN: best practices call for thorough research and analysis of a variety of factors prior to procuring and deploying a DAM system. Identifying key business needs, determining the problems you are trying to solve, articulating goals, selecting success criteria, and calculating potential ROI during this stage provides the foundation needed to present a solid business case. Designating a team led by a DAM champion and identifying available resources to meet stated goals both informs and enables success within every stage afterwards.

- ASSESS: prior to researching DAM vendors and their wares, this critical stage includes thorough requirements gathering, content auditing, and analysis of DAM Maturity. Within this stage, the development of representative use cases and scenarios supports the identification and prioritization of relevant system requirements. Use of the DAM Maturity Model enables one to measure the current situation and future progress against external benchmarks.

- PROCURE: much has been published on the vendor procurement process, so there’s no need to repeat it here. It should be noted however, that industry analysts also advise their clients to perform a thorough needs analysis and develop use cases/scenarios prior to engaging in research toward the procurement of a DAM system.

- DESIGN: designing an effective metadata, taxonomy, and search architecture and integrating these elements successfully within an intuitive user interface is absolutely fundamental to managing digital assets effectively and enabling users to find the assets they need. Developing standards along with supporting policies and procedures enables effective governance of assets and their metadata. Although it is surely tempting to start tinkering around with system configuration options in order to get a DAM system up and running sooner rather than later, Irena Guseva explains why getting this stage right is so important prior to system implementation.

- CONFIGURE: now it’s finally time to fire up a DAM system and configure it according to the decisions made throughout the previous stages. The technical tasks of installing, configuring, customizing, and integrating a DAM system with other software take place at this stage.

- INGEST: after building a system that is optimized to meet users’ needs, the time arrives to populate a DAM system with assets and their associated metadata. This stage often involves asset and metadata migration—which can often be considered projects in themselves! While automation and batch processing make the ingestion process less painful, there is likely to be significant manual massaging, mapping, and cataloging of metadata from legacy systems.

- DEPLOY: at last, the time to launch a DAM system arrives. Best practices advise a phased approach, piloting the system initially with a relatively small group of guinea pigs to identify and resolve any kinks prior to rolling out the system across an organization. Each launch should be accompanied by ample user training and solicitation of feedback from users. Undoubtedly, pilot projects will reveal the need to revisit and rework tasks undertaken within previous stages until the DAM system is effectively addressing the major pain points identified by users during the assessment stage.

Ongoing considerations and processes:

- CONSIDER: the DAM Maturity Model provides a holistic framework that can be used throughout an entire initiative as a guide to developing maturity across the entire DAM ecosystem. With 15 dimensions mapped across four categories (people, processes, information, and systems), the DAM Maturity Model supports the effective management

of assets throughout their entire lifecycle. - EMPLOY: throughout a DAM initiative, comprehensive project management orchestrates all the pieces of the puzzle that need to come together, while effective change management reconciles the conceptual and practical gap between the past, present, and future that can easily tear an initiative apart. Taking the time to document all of the standards, policies, and decisions made throughout the previous stages will go a long way towards supporting training and governance programs. All along the way, advocacy and promotion serve to garner support and sustain momentum for the initiative.

Ongoing management and governance:

Once a DAM system is up and running smoothly, the official implementation, or DAM “project” may be considered finished. The practice of digital asset management, on the other hand, is an ongoing process that requires ongoing management and governance of the people, processes, information, and technology that interact within a DAM ecosystem.

As time passes, employees come and go, companies merge and split, business priorities change, and new technologies emerge. DAM systems and strategies need to change as well. Users need to be kept informed of new capabilities, upgrades, new collections, adjusted workflows, and new policies. As new users come on board, they need to be trained and supported. Workflows need to be optimized, cataloging needs to be audited, metadata schemas and taxonomies need to be updated, and DAM systems themselves eventually need to be upgraded and possibly integrated with other technologies. And because there is never enough time, staff, or budget to go around, ongoing advocacy is required to maintain support for the effective management of digital assets across an organization burdened with a legion of competing priorities.

Preventing the “failure to launch” scenario

Now that we have a roadmap to visualize the various stages of typical DAM initiatives, let’s take another look at where DAM initiatives typically break down along the way. In David’s initial call to action, he framed the value of information professionals around the discussion of what could go wrong if a DAM system isn’t properly configured. Back in 2005, Linda Tadic also advocated for the importance of library science skills when configuring the information architecture of DAM systems. As evidenced in Table 1 below, poor information architecture (taxonomy, metadata, and search) is only one of many failure points. In fact, the failure points are heavily concentrated in the beginning planning stage and in the ongoing requirements that come into play after a DAM system is rolled out to users. Notable as well are the failure points dealing with inadequate information and needs assessment, and the ineffective structuring of data.

| Reason for failure | Stage |

| Lack of executive buy-in/sponsorship | Plan |

| Lack of ownership and decision making | Plan |

| Inadequate/misaligned staffing | Plan |

| Unclear goals | Plan |

| Inadequate analysis of workflow and information needs | Assess |

| Misaligned vendor/system technology | Procure |

| Ineffective data structuring | Architect |

| Inadequate arrangement and description of assets | Govern |

| Lack of training, follow up, and ongoing evaluation | Service |

| Inadequate reference (support) services | Rollout/Service |

| Inadequate access to needed assets | Manage/Govern |

| Inadequate stewardship of the asset collection | Govern |

| Lack of outreach and advocacy | All stages |

| Inadequate change management | All stages |

Table 1: Failure points mapped to DAM initiative stages

Certainly, information professionals can use their skills in metadata, taxonomy, search, and interface design to configure a DAM system that aligns with users’ information needs. Although this is the most obvious stage where an information professional can quickly and visibly provide a high ROI for employers, the skills of today’s information professionals are more widely applicable and can be exploited long before and after this stage of the game. In fact, information professionals are the ideal people to champion DAM initiatives throughout the entire process—and beyond.

Drawing on their deep understanding of human information behavior as well as knowledge of how data and information is stored, accessed, used, and exchanged across within and across information systems, information professionals represent the ideal bridge between users and information technology. With the ability to architect information systems and instruct all types of users on how to access and use them effectively, information professionals are uniquely suited to work across organizations in order to plan, coordinate, manage, evaluate, and govern DAM initiatives:

- During initial planning, information professionals can naturally take on the roles of DAM Champion, information specialist, DAM administrator, and educator (four for the price of one!). Designating ownership to professionals who can cover all of these roles together will go a long way towards making an effective business case and securing executive buy-in (based on reduced overhead, if nothing else). Down the line, this can also streamline communication and facilitate efficient decision making, which are significant failure points encountered during this stage.

- When assessing needs and identifying requirements, the primary failure point identified earlier was inadequate analysis of workflow and automation needs. Pannuto (2005) maintained that this phase is the most important for a successful implementation, stating that “….we don’t learn the business well enough to fully understand the cultural changes needed to implement a successful DAM solution” (p. 13). Here, information professionals can leverage their skills in identifying users’ information behavior both directly through reference interviews and indirectly through search logs and other sneaky methods such as watching users work. Analyzing the flow of information through various systems and channels, and inventorying large stores of content are challenges that information professionals particularly enjoy tackling. On a macro level, the information collected can be used to determine levels of DAM Maturity and how a DAM initiative can support an organization’s broader digital strategy. On the micro level, the insight can be used to create representative use cases and scenarios that can identify potential areas for automation and integration—which also inform system requirements for the next stage.

- When it comes time to procure a DAM system, information professionals can use their skills in evaluating information systems to align users’ needs and requirements with the capabilities of specific DAM products or platforms. They can help answer questions like: does a system support hierarchical or flexible data models? What does “support for controlled vocabularies” mean? What types of filtering are offered for drilling down through assets quickly? Can indexing and relevancy ranking be tweaked? Are taxonomies integrated fully into the search presentation? The answers to these questions have a significant impact on findability and user experience, and can make or break user adoption. Information professionals can save significant implementation time up front by determining if vendor technologies live up to marketing hype.

These evaluation skills can also benefit DAM vendors looking to secure a competitive advantage within the crowded and fragmented vendor landscape, as David suggested. DAM veteran Lisa Grimm also recently commented on the benefits of capitalizing on these evaluative skills:

“It seems that one solution would be for DAM vendors to seek out long-term DAM managers and librarians for product management roles – people who live and breathe the tools, and who understand the importance of standards – to really push the next generation of DAM solutions” (2015, para. 5).

- When designing the information architecture for a DAM system, the expertise of an information professional is invaluable. Metadata, controlled vocabularies, search, and the user interface are key components in the effective structuring of information for findability—and where the skills of information professionals truly shine. While text analytics techniques are valuable for deriving meaning from unstructured data within text based documents, when it comes to findability for rich media assets, metadata reigns supreme. This is where information professionals easily earn their keep and demonstrate most visibly why they are worthy of the DAM Whisperer moniker. Appropriating longstanding and proven techniques of knowledge representation developed over centuries within the LIS community, information professionals can whip content into shape by:

- Designing metadata schemas using both core standards to support federated search across multiple collections as well as industry-wide and local standards to support discovery within specific contexts. Information professionals are experienced in modeling data with findability and preservation in mind, and documenting those schemas within data dictionaries and metadata registries. Mixing and matching schema standards, crosswalking legacy metadata, and linking data to controlled vocabularies are well known and time tested strategies used by information professionals to balance local needs for granular, descriptive metadata while also supporting data exchange and federated search across external systems.

- Designing and integrating an enterprise-wide taxonomy to facilitate navigation, browsing, and enterprise search across not only a DAM system, but also across a variety of data and content management systems.

- Developing and integrating taxonomies and controlled vocabularies with the search functionality of a DAM system. Why settle for just folder browsing when you can also use dynamic faceted browsing and faceted search to filter through your assets by a number of different attributes that leverage both metadata and unstructured text? When taxonomies, thesauri, and search are fully integrated with a DAM system, users don’t need to guess what terms are used in a DAM system and what types of related content might be available. Synonym control, autocomplete, guided search, and other techniques that users expect from their consumer experiences should be a given.

- Finding the right balance between standards and localization, control and flexibility, recall and precision, access and security—not to mention the project triangle, is a challenging task that requires knowledge of how DAM systems work, how to structure information for findability, users’ needs, and many more variables that must be tailored to specific business rules and workflows. Information professionals truly live for these challenges!

- When it comes time to configure a DAM system, information professionals can set appropriate levels of access that reflect business rules, security protocols, workflows, and compliance with intellectual property laws. Their broad, neutral perspective makes them highly suited to effectively engaging with users from all departments and units as well as external partners during system customization and integration.

- When the time for ingestion arrives, the specialized skills of information professionals can be put to good use mapping schemas, cleaning and wrangling data, and of course, cataloging assets. Information professionals have expertise in designing metadata schemas and using controlled vocabularies along with data content standards that support the production of consistent, quality metadata. Because data is often shared within and among organizations within the cultural heritage sector, information professionals are well versed in best practices for structural, syntactic, and semantic metadata interoperability. They know that digital asset management is not equivalent to digital preservation—and that assets and their associated metadata need to be managed throughout the entire curation lifecycle.

- During deployment, information professionals can leverage their reference interview skills to solicit user feedback that will identify and help resolve system configuration, integration, and information architecture issues. When a DAM system is ready for rollout, information professionals can use their instructional skills to train users at all levels on how to access and use the system effectively. Group demonstrations, workshops, one-on-one sessions, interactive tutorials, and technology support have always been part of their job description.

Throughout an entire DAM initiative, information professionals:

- Consider how people, processes, information, and systems intersect, using the DAM Maturity Model to provide a solid framework to ensure that all of these factors are balanced and aligned with external benchmarks every step of the way.

- Employ project management and change management principles and practices to keep an initiative on track and users engaged throughout the entire process. In a DAM Guru interview last year, Holly Boerner shared numerous pearls of wisdom related to the importance of the “people” part of the DAM equation:“….typically the success around a digital asset management project is going to be tied to how well the initiative is integrated with its user base. How the DAM leadership handles change management, how they get people on board (or not), and the ongoing tight rope walk that can be…the audience/people factor is not to be underestimated” (2014, para. 11).“I think a big challenge is getting corporate cultures to appreciate and understand that “digital asset management” is the work done in managing assets and info and workflow—the strategizing and system admining and all the rest, and that “digital asset management” is NOT just the technical solution put into place in an environment….I’ve seen powerful, beautiful, expensive systems mis-implemented or orphaned because a company’s not willing to investment in the humans, and human expertise required to make sure a system’s leveraged properly and evolved in sync with the environment it lives in (2014, para. 14-16).”

Documentation, a critical and often thankless task, is a core competency for information professionals. Information professionals use documentation of standards, policies, procedures, surveys, content audits, technical specifications, and more to support instruction and technical training. Information professionals are also certainly no strangers to advocating and promoting the benefits of using information systems effectively.

The ongoing management and governance of a DAM program requires full time attention, and many practitioners and industry analysts have pointed out that this is where many DAM initiatives fall apart. After a DAM system is deployed, information professionals can and should remain at the helm in order

to manage the long term access, arrangement, description, and stewardship of digital assets while evaluating, promoting, and advocating for the DAM system and the services that connect users with the critical information they need.

As neutral parties, information professionals can manage and govern DAM programs with an eye toward the bigger picture, balancing the needs of individuals with the needs of the organization at large. They know that answering the question, “what’s in it for me?” is critical to the success of any DAM advertising campaign. Information professionals are adept at using every user interaction as an opportunity to collect user feedback in order to improve a system and supporting services. With experience administrating a broad range of information systems, information professionals are fluent in database reporting at the system, user, and asset level to provide metrics that can be used (in combination with search logs, user interviews, and other measures) to help identify when standards, workflows, policies, and information models need to be evaluated or changed.

Long term metadata management and governance is an area of particular significance, since metadata is the foundation digital asset management. As Avalon consultant Demian Hess and many others advise, “Don’t look at metadata collection and management as a one-time project. It is a vital part of your business and needs to be treated as an ongoing function” (2015, para. 11). Despite automated technologies, metadata expertise is still required to assign meaning and context to digital assets.

Skilled at training, reference, advisory, troubleshooting, and documentation, information professionals are well positioned to provide ongoing service and support to users. Because they are passionate about using technology to connect people with information, ongoing advocacy and promotion are always part of their ongoing strategy to help users adopt new workflows and achieve greater efficiencies in their work.

LIS skills in action

Although mapping the skills of information professionals to the stages of a typical DAM initiative is an informative exercise, to really get a sense of how these skills can be leveraged across various industries and in support of diverse use cases, I point readers to some of my favorite case studies involving information professionals (my apologies in advance…not all of these articles are open access):

- Conducting a metadata audit in a broadcasting environment (Tadic, 2014)

- Metadata overhaul: Upgrading metadata in the University of Houston Digital Library (Thompson & Wu, 2013)

- Digital Asset Management: Where to Start (Megan McGovern, 2013)

- 10 Museums, 12 Months, 1 DAMS: Adventures in centralized systems at Balboa Park (Goldstein & Sully, 2012)

- UCSF School of Pharmacy digital assets taxonomy and metadata development (Busch, Davila, Farm, Lauruhn & Levings, 2012) [related presentation]

- The role of librarians in DAM projects (Deb Hunt, 2012)

- The sorting of competing metadata models in digital asset management (Barnes, Bowden, Griffith & Keathley, 2011)

- Video metadata modeling for DAM systems (Bachman, 2010)

- Unnamed things: Creating a controlled vocabulary for the description of animated moving image content (Luckow, 2010)

- Digital asset management case study – Museum Victoria (Broomfield, 2009)

- Building a keyword library for description of visual assets: Thesaurus basics (Slawsky, 2007)

Hiring Manager: “Wow, that sounds great. Can you help with our larger digital strategy too?”

Info Pro: Although information professionals make ideal DAM Whisperers, they also have the potential

to provide significantly more value when one considers that DAM exists within a much larger, developing ecosystem—one in which information professionals are poised to become strategic players.

Adjusting our DAM lens

Businesses are increasingly recognizing the value of information and the competitive advantage awarded to organizations that can leverage end-to-end digital supply chains to transform data into information—and ultimately into business intelligence. The increasing demand for real-time, personalized data to inform strategic business decisions requires the ability to aggregate, store, curate, analyze, visualize, and distribute vast quantities of both structured and unstructured data throughout the enterprise and beyond—which in turn requires interoperability among any number of internal and external information systems, protocols, and services. The evolution towards centralized enterprise platforms and services will have a profound effect on DAM technologies, along with implications for the value of information management. With this in mind, a tour of this evolving landscape is definitely in order…

Focusing our lens first within the DAM community, we see increasingly impassioned discussions on the topic of interoperability. These pointed conversations are being initiated in an effort to spark the development of innovative solutions to address the challenges of integrating DAM systems and processes within the current environment of digital disruption. The conversation often centers on the need to integrate DAM systems with various types of business data to enable a more seamless flow of information throughout the enterprise. DAM vendors and analysts in particular discuss interoperability within the context of agile marketing and digital experience delivery, which is where DAM is often seen

to have the most impetus. Integration strategies typically involve integrating DAM systems with various types of business systems and platforms (WCM, PIM, ERP, CRM, and many more) to push and pull data back and forth to each other, as depicted in the Real Story Group’s Marketing Services Reference Model (seen in this webinar at 7:51).

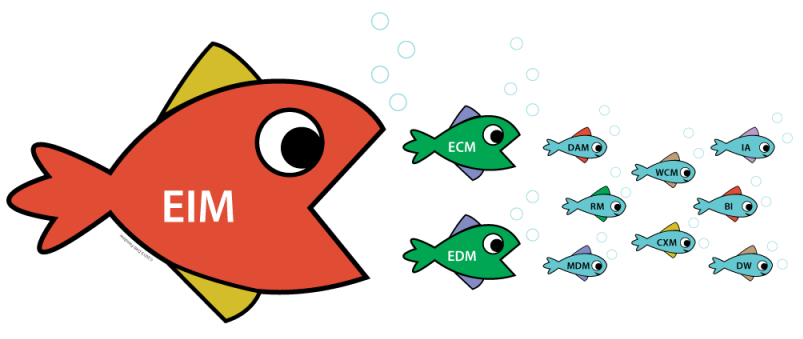

Pulling back our lens a bit to focus on the broader Enterprise Content Management (ECM) perspective, where DAM lives conceptually, despite its niche market status. The AIIM ECM Roadmap frames DAM systems as just one type of content management repository alongside file systems, databases, and data warehouses that store content which has been extracted, ingested, indexed, and categorized from within a variety of business applications. Within this model, library services are conceptualized as intermediary processes which facilitate collaborative workflows and business processes between content creation and content storage technologies.

Moving our lens sideways just a smidge, we find the overlapping universe of Enterprise Data Management (EDM). The DAMA-DMBOK2 framework uses Data Management as an umbrella term, positioning content management, metadata management, and supporting technologies as integrated functions within the domain and practice of Data Management.

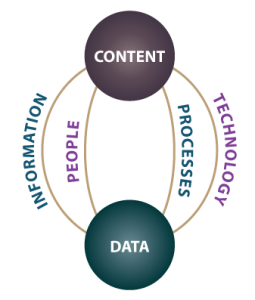

While both the ECM and EDM frameworks integrate the management of data and content to some extent, both models still maintain a content- or data-centric view. However, when we pull our lens back one more notch, we discover an even larger ecosystem taking form.

Digital’s gravitational pull

If scientists aimed their powerful telescopes at the center of the information universe, they might find evidence of a super black hole at its center, sucking up planets, stars, and zettabytes of Big Data along with it. If they had access to some seriously advanced time-lapse technology, they might have captured a spectacular cosmic event—the demise of planet data and planet content in the battle against digital gravity. Perhaps they might have witnessed the moment when these collegial planets traveled beyond the event horizon, triggering a magnificent quasar which swallowed the planets whole and spit them back out into space as the resident twins within a new galaxy, littered with bits and bytes of Big Data twinkling by the billions. Even though the black hole itself would have eluded discovery, scientists would not have been able to refute the evidence of its existence as they marveled at the two planets orbiting in newfound alignment, held together in a delicate equilibrium by the interdependent forces of people, processes, information, and technology:

Scientists would no doubt have immediately composed the following tweet, using a new acronym that could serve as an umbrella concept (and an indexing term) with which to emphasize the newfound kinship between both planets: “Eureka! The planets have aligned! Data by itself has no value, and content without governed data is meaningless. It’s the dawn of a new #EIM era.” And so, ever after, organizations looked to the Enterprise Information Management galaxy as a beacon of light within this new universe…

The Enterprise Information Management Ecosystem

David Marco (2007) defined Enterprise Information Management (EIM) as:

“….the systematic processes and governance procedures for applications, processes, data, and technology from a holistic enterprise perspective. The purpose of enterprise information management is to bring enterprise order, purpose, structure, efficiency, and performance to applications, processes, data, meta data and technology” (para. 4).

Cagle (2014) described the forces that are driving the alignment and convergence of data- and content-centric frameworks towards the more holistic approach of information management:

“During the decade from 2000 on, data began moving between departments within an organization, and while you saw some movement towards extending this out to supply channels and downstream to select data consumers, most of the growth in that period involved data communication growing up out of the divisional silos to become enterprise data. Increasingly, that data is spilling over the enterprise walls (like water flooding a valley) towards a wide number of consumers, many of whom have different needs, and all of whom need not only the raw data but also the metadata” (para. 6).

There are various conceptual models and related methodologies that describe and support the EIM framework. I present them briefly here in order to highlight the critical position in which information management principles and practices are situated within this larger ecosystem.

In the first issue of EIMInsight Magazine, Mike Jennings (2007) outlined the EIM framework, which places all types of data in the familiar foundational position within the data stewardship “house,” followed by information security management. Next up comes metadata management, which along with information architecture sandwiches a host of data and content management components. Ruling the roost at the top is data governance. Within this model, information management maintains a strategic position, as metadata management and information architecture sit across every functional component that involves the management and storage of all forms of data and content—and business intelligence initiatives as well.

Forrester’s “barbell” presents another view of EIM that emphasizes the relationship between data management and content management, and outlines the foundational elements required to support an integrated EIM ecosystem. In 2013, Weintraub, Owens, and Jedinak introduced the following definition of Enterprise Information Management within a Forrester whitepaper:

“Enterprise information management (EIM) encompasses the processes, policies, technologies, and architectures that capture, consume, and govern the usage of an organization’s structured data and unstructured content. EIM enables businesses to derive more value from their data and content, harmonizing what has traditionally been a dichotomy. Forrester proposes a logical representation for EIM that unifies data management and content management [emphasis added] using a common set of foundational technologies” (p. 1).

The following year, Weintraub (2014) asserted that a first step in building an EIM ecosystem is to invest in the foundation:

“An EIM strategy is founded on data and content repositories and a cloud-based infrastructure that components will access using application programing interfaces (APIs), dedicated services, and different security mechanisms….Foundational technologies present the best opportunities for enterprises to begin to build their EIM capabilities.” (p. 2).

As readers learned in the third part of this series, skills in search and discovery, taxonomy, archiving, classification, governance, library services, migration, records management, and metadata management are all core competencies for information professionals. And these skills represent a large portion of the very foundation that holds up Forrester’s EIM model.

Last but not least, the MIKE 2.0 methodology includes a set of solutions that incorporates a view of information as an asset itself with its own lifecycle that needs to be managed and governed alongside both data and content. The MIKE 2.0 methodology proposes the development of an Information Development Leadership Team, which includes an Information Architect as part of the enterprise architecture team and five roles within the development team—four of which could be filled by an information professional.

All of these enterprise information management frameworks clearly illustrate the need to invest in the expertise of information professionals. As illustrated within all of the above models and methodologies, in order to turn data into information and in turn, transform information into business intelligence, the skills of both data and information professionals must be employed across departments and functional areas within organizations.

The conversation heard ‘round the world

Moving from theory to practice, it seems that today, practitioners within the data management and content management fields are often attending different conferences and writing for different audiences. Considering the parallel placement of data and content with the EIM framework, it’s not surprising to see the same topics and issues threaded throughout both industries’ conference agendas, publications, and virtual watercooler conversations. Within both arenas, one can see the same calls for interoperability, standards, data security, workflow efficiency, data/metadata governance, change management, project management, and so on.

Familiar conversations are occurring across both industries in regard to how both data and metadata are stored, modeled, managed, associated, analyzed, and distributed throughout the enterprise—and beyond its borders. For example, similar to discussions on the need for structured metadata and taxonomy prior to implementing DAM systems, Kurt Cagle of Avalon Consulting commented that most Master Data Management (MDM) products fail because organizations don’t work on designing enterprise-wide vocabularies first. He explained that:

“Many organizations are now facing (or will soon face) a metadata crisis. As business units evolve and data software and systems emerge to solve specific problems, they introduce explicit models about the things that this business cares about. Yet because most relational databases are intended to solve specific needs, these models about the very same things are disconnected from one another….Organizations have started employing Master Data Management solutions to track keys across systems, but this process is at best a stop-gap, useful for synchronization but because of that ill-suited as a queryable repository.” (2013, para. 15).

And another familiar message for those who promote the value of adding metadata to content—IBM Senior Program Director James Kobielus (2014) likewise described the value of structuring data along with metadata throughout its lifecycle in order to create value:

“Data is useless if it lacks structure or if there is no opportunity to add structure downstream so that it can be processed, analyzed, and delivered into real-world applications….Structure is the contextual matrix within which data’s value is realized. It refers to the formats, schemas, models, tags, ontologies, patterns, and other artifacts without which data is a useless pile of raw bits….only possesses value if there’s sufficient metadata and other contextualizing artifacts to realize value in use” (para. 1-2).

Just as the challenges of managing, sharing, and preserving digital data are leading to convergence across sectors (as explored in the second part of this series), these same issues are now resulting in a convergence between data and content management domains:

Peter Morville, one of the founding fathers of the field of Information Architecture, reminds us that:

“Where we sit relative to our colleagues can unlock creativity and drive collaboration….how we frame our work changes its outcome….Ontology begins with the org chart. In making frameworks for collaboration, we must think about goals, metrics, roles, and relationships, because how we organize ourselves changes everything” (p. 69; 46).

To realize the potential of EIM, Morville’s insight on systems thinking deserves attention. Identifying how information—and most importantly, people and teams—are organized to either support or hinder the interwingled touchpoints, flows, loops, forks, and dependencies within ecosystems is critical to the success of any type of information management initiative.

Instilling family values

What does the unification of EDM and ECM frameworks have to do with the value of information professionals? Everything. If both sides of the data and content management coin are not aligned and supported with the equal valuation of the foundation (technology, information, people, and processes), then the very infrastructure of the EIM ecosystem will remain eternally imbalanced and dysfunctional.

The cohabitation of data and content should come with a dose of unsolicited advice from well meaning parents. As authority figures, “mother” information and “father” technology need to provide the structure, guidance, security, direction, and loving discipline that is so critical to navigating any codependent relationship. Valuing information alongside technology instead of relegating it to the level of those pesky, high-maintenance in-laws that are rarely invited to dinner anymore will in turn increase the value of content repositories (such as DAM systems) that structure and provide mediated access to information.

Information systems—whether they manage data or content, are supported by both technology and the information architecture that structures and provides context for the information stored inside of them. Without both legs to stand on, an information systems simply becomes another digital landfill. This point was driven home by Roe and Loshin within a 2013 Dataversity survey that examined the use of information architecture at the enterprise level:

“….where Data Architecture is necessary to contain and organize the manifold data resources into a manageable system, Information Architecture is necessary to combine those resources into a structure that allows the dissemination of that information to be captured, shared, analyzed, utilized, and governed throughout an enterprise, across all lines of business, within all departments, with confidence and reliability” (Roe & Loshin, p. 8).

The undervaluation of information management and the artificial separation of data and content along with information and technology within our industries, academic disciplines, and professional communities threatens the success of every component within the EIM ecosystem. Case in point: the mating of Marketing and Advertising with IT to produce “Martech” and “Adtech” offspring. Although these terms are certainly catchy and the need for embedding technology throughout the enterprise is undeniable, the “Information” part of “Information Technology” seems to be largely ignored within these nascent hybrid communities. Along a similar vein, visions of a unified “data supply chain,” often continue to be promoted as achievable simply through the use of a technology platform—without any mention of the critical role that information management plays in structuring, organizing, and governing the data within it.

As the principles and practices of EDM and ECM converge in support of the EIM vision, information architecture will increasingly be revealed as a critical enabler that either makes or breaks a successful EIM infrastructure. If the value of information management remains but an afterthought as communities of practice come together, EIM initiatives will fail for the same reasons as explored earlier in regard to DAM initiatives. How the EIM framework is adopted in practice will have long lasting repercussions—not only within individual organizations, but also across industries and professional communities.

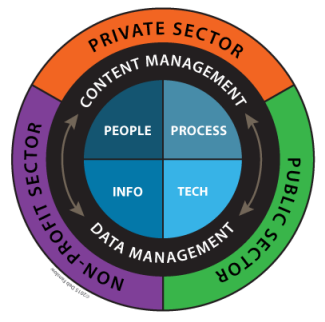

We’re all in this together…

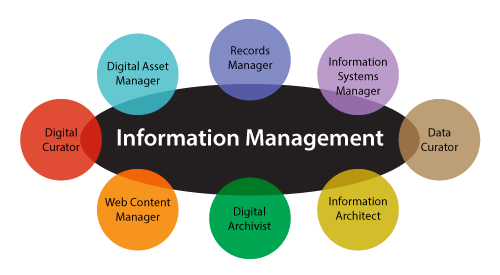

As much as I love how Forrester’s dumbbell model emphasizes the connection between data and content as well as the core information and technology elements needed for the realization of an EIM ecosystem, I wondered what this concept might look like when placed within the context in which it is practiced. So I went ahead and took the liberty of creating yet another perspective of EIM which is complementary to existing EIM models, but also broadens their scope a bit. I added the people and process components from the DAM Maturity Model to Forrester’s foundational information and technology components, and positioned them at the core of EIM practice across all employment sectors. This is what happened:

The above model (Information Management Utopia?) both simplifies and expands Forrester’s barbell. Eliminating the specific elements involved in data and content management allows for focusing instead on the fact that data and content are components within the same information lifecycle. Arranging the employment sectors along the outermost circle expands on Forrester’s EIM framework and emphasizes the fact that every sector is dealing with this same ecosystem, although within different contexts.

Within the LIS community, the same principles that facilitate the interoperability of metadata—simplicity, extensibility, centralization, modularization, and standardization—also work for systems, vocabularies, processes, and even communities of people. While I have been accused of being overly idealistic on occasion, the sociologist in me cannot dismiss a potential pattern of behavior:

- As the EIM framework slowly gains traction, an inclusive vocabulary is emerging that more fully incorporates Kampffmeyer’s “Pyramid of Knowledge” (slide 14). In a 2013 keynote presentation at the OpenText EIMDays conference in Munich, consultant Ulrich Kampffmeyer, a leading proponent of the EIM framework, stated: “There is no sense in naming solutions or industries by the type of information they intend to manage. Todays solutions must be able to manage every type of information” (slide 17).

- AIIM leader John Mancini’s forecast for 2020 just recently declared that: “ECM as we know it will be gone…. Content will be everywhere and in everything, but Content Management will be increasingly invisible…. The term “ECM” is past its prime as a description of the revolution that is being driven by Mobile, Analytics, Cloud and Collaborative technologies…. A new “umbrella” term is needed. ECM needs to become PART of the puzzle, rather than the puzzle itself” (p. 2, 9).

- The Data Management community is embracing EIM in practice, as this year’s Enterprise Data World (EDW) conference brought with it the announcement that DAMA International is merging with the MIKE 2.0 Governance Association, an open source EIM delivery framework.

- Cagle recently reported on the trend of including librarians and archivists on Data Science teams.

The last two examples in particular are encouraging for the successful realization of EIM, as they indicate that information is beginning to be recognized as an asset in and of itself, and that the skills of information professionals are becoming more highly valued within the Data Science community. If these type of trends continue, the lines between the employment sectors in the above model will become porous, providing exciting opportunities for mutually beneficial partnerships, initiatives, and outcomes within and among all sectors.

The enterprise interoperability imperative

Many IT analysts and consulting firms are advising organizations to adopt an EIM framework, and professional communities are gearing up for change. Information architects have recognized the applicability of their skills across this emerging ecosystem, and they are retooling and rebranding themselves to remain as valuable within this broader ecosystem as they have been within web design and development.

Digital’s gravitational pull is increasingly being recognized by residents within the data science community as well. Moving beyond abstract models, Gartner’s Enterprise Information & Master Data Management Summit aims to put the EIM framework into action. Having broadened the scope from MDM to EIM in 2014, topics such as metadata management and information architecture can now be seen on the menu alongside data management topics.

Although not often mentioned by name, the EIM framework is increasingly being recognized within the DAM community. As mentioned earlier, industry analysts such as the Real Story Group have been advising the DAM community to view DAM within the broader enterprise data ecosystem, reporting on the need for integration not just with CMS systems, but also with the legion of systems involved in the marketing automation toolbox such as analytics programs, PIMs, CRMs, DMPs, and more (Regli, 7:51). In a recent and highly cited article, John Horodyski remarked that:

“Any successful DAM implementation requires not just new technology but a holistic digital strategy that integrates with the enterprise’s ecosystem to generate revenue, increase efficiencies and emerging market opportunities….Working across the enterprise to get the digital house in order allows for delivery of assets to multiple channels and partners with diverse requirements. The diversity of input also increases the ability to be prepared for the future” (2015, para. 3, 12)

Ralph Windsor and the staff at DAM News have written extensively on the need for integration and realization of a “digital asset management value chain.” Recently, while acknowledging Horodyski’s article as evidence of an increasing awareness of this issue, Windsor stressed the need for the entire DAM community to understand the implications of the larger ecosystem in which DAM lives:

“The problems in the DAM software industry are essentially architectural in nature….Enterprise Digital Asset Management is becoming more like a logistics challenge: supporting DAM infrastructure of core services through to integration and then front-end interfaces, plus all points in-between…. It is about seeing the architecture of the overall solution and not only that, but the business impact at each different level” (2015, para. 15-17).

Vendors across the information management landscape are cognizant of the big picture and are scrambling to re-architect, redefine, and rebrand their offerings to support an end-to-end digital data supply chain. Within Jeff Lawrence’s recent vendor roadmap survey, DAM vendors established that they are well aware of the interoperability imperative. Within this survey, Leslie Weller of Canto described the position of DAM within the EIM universe:

“The future of DAM looks like an integrated enterprise digital ecosystem where systems talk to each other and share data in such a way that moves organizations closer to a 360 degree view of their content — that is, improving transparency of the entire content lifecycle and deriving actionable data accordingly” (2015, para. 14).

All roads lead to…standards

Although DAM vendors’ product roadmaps will surely show different paths to realizing EIM, they too will not be immune to digital’s gravitational pull. The need for modularity, flexibility, and extensibility in the name of interoperability demands standardization. And standardization requires cooperation—the real challenge in a competitive, disrupted marketplace. If the industry pundits are right, as the need to aggregate, manage, analyze, and distribute both data and content within the enterprise comes to a tipping point, Enterprise Information Architecture (EIA) initiatives will gain traction, as well as the need for standards.

Since there are already standards for structuring, transmitting, harvesting, aggregating, and presenting data, the low hanging standards fruit has already been picked. Although there are standards at the bottom for structuring data within databases, and standards at the top for presenting data within applications, the middle metadata layers remain murky. The last frontier is the application of standards and governance to content within the systems and applications in which we describe and add context to our unstructured data. This is where data structure (schemas), data values (vocabularies), and data content (cataloging rules) become invaluable for providing semantic context to disambiguate the inherent ambiguity of the languages we use to represent knowledge. It is within this last frontier that the value of information professionals’ skills in structuring, organizing, and managing content becomes irrefutable.

Then along came spider, spinning a new Web

Although the full realization of the Semantic Web has been the subject of much dispute, the marriage of semantic technologies with NoSQL databases has created new methods for structuring, managing, and integrating heterogeneous data across disparate information systems. Flexible metadata models and the ability to define and infer relationships among entities and their attributes beyond classic three-way thesaural relationships has resulted in growing adoption of these technologies. RDF, OWL, and SPARQL are acronyms that will no doubt increasingly be making appearances at a DAM conference near you.

Pete Stiglich (2010) described how semantic technologies can be used as tools to manage and analyze metadata across heterogeneous sources and systems through the querying of data that has been translated into RDF using OWL vocabularies—which essentially functions as a switching language. In a land of data and content silos, semantic technologies represent a viable path to realizing EIM capabilities without leveling an organization’s entire information architecture infrastructure. And interoperability is not the only benefit of semantic technologies. Cagle (2013) explained the potential of these technologies to uncover both explicit and implicit relationships between isolated data through the power of inferencing:

“Perhaps what makes semantics so exciting in the space of metadata management is that it becomes increasingly possible to combine semantics with search. Not all metadata is in relationships – in almost any system, titles, descriptions, abstracts, body copy, summaries, biographies and other narrative content also contain relevant information about certain resources. Textual searches, field (or element) searches, lexicons and thesauri can match text query strings and identify candidate fragments, then semantic solutions can use inferencing logic to eliminate those things that aren’t relevant to the item while finding relationships that may extend across four or five (or even dozens) of links between documents” (para. 15).

Now, while new data models emerge and automation technologies continue to advance, the fact is that data—whether relational, hierarchical, or semantic—still has to be structured somewhere along the pipeline in order to transform it into information and business intelligence. Data still needs to be described, ontologies still need to be designed, relationships still need to be defined, algorithms still need to be trained, users still need to be educated, and even automated data still needs to be governed in order to reap any informational rewards. And because every data model has both benefits and drawbacks within specific contexts, instead of supplanting existing data models, the semantic data model adds yet another layer (or graph, if you will) of data to contend with on top of the mountains of data that organizations are already struggling with.

As Boerner (2014) wisely commented, “A hundred people on a bus is unquestionably a more efficient means of transportation than a hundred people driving a hundred cars…but you still need a bus driver or two” (para. 16). Just as with DAM initiatives, data/metadata management and governance is critical to the success of any information ecosystem. And considering that ontologies are controlled vocabularies in their most complex incarnation and they are critical to implementing the RDF framework, their design requires the expertise of professionals skilled in constructing data models and integrating them with complex vocabularies. This inevitably brings us back to…

Investing in the foundation

So, after all is said and done, why hire an information professional? Because modern information professionals are not just strategic enablers for successful DAM initiatives—they also possess untapped expertise that is essential in realizing the effective management of information across the enterprise. As cross-disciplinary, cross-departmental, cross-functional facilitators, information professionals are uniquely suited to collaborate with diverse stakeholders to ensure the alignment of data and content, information and technology, and people and processes across the enterprise. And because all information professionals are trained in the underlying principles of information management, they are strategically positioned to partner and collaborate with any number of information professionals who may be already involved in the curation of data and content within an organization.

Data curator, archivist, information architect, digital asset manager, their title doesn’t matter—information professionals all speak the same language and possess the same core LIS skills that are essential to supporting and sustaining an EIM ecosystem. Bring these professionals together as part of an EIM team, and there’s no telling what might happen.

Hiring Manager: “Well, I think that covers all the bases. Do you have any questions for me?”

Info Pro: Although this article certainly contains enough quotes, it seems appropriate to end this series with some compelling statements I came across recently. First, in a vendor sponsored white paper entitled Why Your Business Users Need to Love Metadata,” Charles Roe reminds us that:

“The wealth of an organization may be shown on balance sheets and in electronic ledgers, but the real fortune is contained within its information assets — its data, the lifeblood that pumps through distributed computing nodes, is stored in data warehouses, analyzed with BI applications, emailed in spreadsheets and documents, created, evaluated, and discussed by knowledge workers every day in enterprises the world over. Knowledge is information and information comes from data; without quality data there is no data governance, no data integration, no MDM, no EIM, no ERP, no CRM, no BI, no more impressive acronyms to discuss in meetings.

The data of your organization is like an enormous cache of gold just waiting to be dug up and refined. To get to that gold out of the ground you need to know where its veins are; you need a structure and a plan. You need metadata….Metadata is the foundation of information management, and without information management, the modern-day enterprise is stagnant.” (2012, p. 1)

And last but not least, consultant Gerry McGovern identified the undervaluation of employees’ time as core to the underlying findability problem within the digital workplace today. McGovern (2015) captured the value of considering findability as a key performance indicator:

“Employees are not looking for miracles. They just want to find stuff quickly. They want to be able to trust that what they find is accurate and up-to-date. They want to be able to do stuff as quickly and easily as possible” (para. 13).

When undertaking an enterprise information management initiative, investing the time and human resources up front to develop a centralized, standardized, and sustainable information architecture will always pay substantial dividends in the long run. Valuing information as a strategic asset provides proven returns wherever and whenever information is reused throughout an enterprise digital value chain. Since information is today’s business currency, I ask then, who doesn’t need a DAM librarian?

References

Boerner, H. (2014). Guru Talk: Holly Boerner – AMEX. [blog posting] Retrieved from guru-profile-holly-boerner/

Cagle, K. (2013). Metadata Management – Semantics for Big Data? [blog posting] Retrieved from http://blogs.avalonconsult.com/blog/search/metadata-management-semantics-for-big-data/

Cagle, K. (2014). Metadata Governance in the Big Data Era. [blog posting] Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20140616220947-5187765-metadata-governance-in-the-big-data-era

Davey, M. (2014). Don’t gamble on your DAM strategy. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://damfoundation.org/?p=31107

Diamond, D. (2014). Library Science, not Library Silence. Retrieved from http://www.cmswire.com/cms/digital-asset-management/library-science-not-library-silence-026230.php

Durga, A. (2012). A maturity model-based approach for DAM implementations. Journal of Digital Media Management, 1(2). 183-194.

Gartner. (2014). Gartner Says One Third of Fortune 100 Organizations Will Face an Information Crisis by 2017. [press release] Retrieved from http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/2672515

Grimm, L. (2015). What’s holding DAM back: Musings. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.lisagrimm.com/?p=604

Hess, D. (2015). Six Pain Points When Managing Digital Asset Metadata. [blog posting] Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/six-pain-points-when-managing-digital-asset-metadata-demian-hess

Horodyski, J. (2015). When You Think DAM, Think Integration. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.cmswire.com/cms/digital-asset-management/when-you-think-dam-think-integration-028304.php#disqus_thread

Jennings, M. (2007). Developing a roadmap for an enterprise information management program. EIMInsight Magazine, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.eiminstitute.org/library/eimi-archives/volume-1-issue-1-march-2007-edition/enterprise-information-management-primer

Kampffmeyer, U. (2013). Enterprise Information Management. [Powerpoint presentation] Retrieved from http://www.slideshare.net/DRUKFF/open-text-eimkeynotekffs20130313

Keathely, E. (2013). Staffing for a DAM: Finding successful digital asset managers. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://damfoundation.org/?p=30926

Kobielus, J. (2014). Big Data Is Not the Death Knell of ETL. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.dataversity.net/big-data-death-knell-etl/http://www.dataversity.net/big-data-death-knell-etl/

Kotrch, S. (2005). Taking DAM risk management beyond the technology: Sources of ongoing business-related risk and practical ways to address them. Journal of Digital Asset Management, 1(5), 323-327. doi:10.1057/palgrave.dam.3640052

Lawrence, J. (2015). DAM’s Roadmap for 2015 and Beyond: Interoperability, Analytics. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.cmswire.com/cms/digital-asset-management/dams-roadmap-for-2015-and-beyond-interoperability-analytics-027641.php

Mancini, J. (2015) Content management 2020: Thinking beyond ECM. [white paper] Retrieved from http://info.aiim.org/digital-landfill/to-content-management-2020-and-beyond

Marck, B. (2015). How to manage a DAM project. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://blog.canto.com/how-to-plan-a-dam-project/?lang=en

Marco, D. (2007). Enterprise Information Management. [blog posting]. Retrieved from http://www.eiminstitute.org/library/eimi-archives/volume-1-issue-1-march-2007-edition/enterprise-information-management

McGovern, G. (2015). Simplicity must be the mantra of the digital workplace. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.cmswire.com/cms/social-business/simplicity-must-be-the-mantra-of-the-digital-workplace-028633.php

Morville, P. (2014). Intertwingled: Information changes everything. Ann Arbor: Semantic Studios

Pannuto, D. (2005). This DAM thing…. Journal of Digital Asset Management, 1(1). 12-15.

Regli, T. (2015). The Right Way to Select Digital & Media Asset Management Technology. [webinar] Retrieved from https://youtu.be/EbC6iKPGdCk

Roe, C. (2012). Why your business users need to love metadata. [white paper] Retrieved from http://www.dataversity.net/why-your-business-users-need-to-love-metadata/

Roe, C. & Loshin, D. (2013). The utilization of information architecture at the enterprise level. [white paper] Retrieved from http://whitepapers.dataversity.net/content31975/

Stiglich, P. (2010). The Semantic Web and EIM: Part 3 – Meta Data Management. [blog posting] Retrieved from http://www.eiminstitute.org/current-magazine/volumn-4-issue-5-october-2010/the-semantic-web-and-eim-part-3-2013-meta-data-management

Three Media Associates (2008). Why DAM projects fail. [white paper] Retrieved from http://www.three-media.tv/documents/White%20Papers/TMA%20WhitePaper%20-%20WhyDAMProjectsFail.pdf

Warwick, J. (2010). Why good DAMs go bad: Building an operational capability. Journal of Digital Asset Management, 6(4), 216-224. doi:10.1057/dam.2010.24

Weintraub, A., Owens, L. & Jedinak, E. (2013) The enterprise information management barbell strengthens your information value. Retrieved from http://www.opentext.com/file_source/OpenText/en_US/PDF/Forrester%20EIM%20Barbell.pdf

Weintraub, A. (2014). EIM Becomes A Reality As Vendors Stitch Together Data And Content Solutions. Retrieved from http://www.opentext.com/campaigns/forrester-eim-white-paper

Windsor, R. (2015). The Need For DAM Architectural Strategy: Seeing The Bigger Picture And Doing Something About It. [blog posting] Retrieved from https://digitalassetmanagementnews.org/opinion/the-need-for-dam-architectural-strategy-seeing-the-bigger-picture-and-doing-something-about-it/

Yakkundi, A. (2013). What is the key to DAM success? [blog posting] Retrieved from http://blogs.forrester.com/anjali_yakkundi/13-09-13-what_is_the_key_to_dam_success

Share this Article:

Every time I read something from Deb, I try to distill it down to a tweet that, when sent, will change minds. I think this way because I know in my heart that the people who *should* be reading this stuff will not read it. Those in charge too often delegate research responsibilities to those who have no skin in the game. And those with no skin in the game tend to be overly influenced by the opinions of those with the loudest mouths.

Still, I can’t help but feel like I need to encapsulate it all into an executive summary. And now, after having read each part of this series, I think I can do that:

The benefit of having a (good) information professional on hand is that it dramatically decreases your chances of falling behind the curve when it comes to having your info ducks in a row. Organizations that do without will eventually get it—they’ll have no choice. But they’ll have to start by catching up for lost time, which will be expensive and time consuming. Organizations that are proactive about this, will be able to benefit from all the advances that are undeniably coming in the areas of information management. These are the organizations that will stay ahead of the curve and, in some cases, define it.

Take, as a comparison example, social media. Those organizations that got the benefits early on gained the most. They got through their awkward tweet stages while few were looking. And by the time any of it mattered, they had followings. On the other hand were the “me too” organizations that popped up Facebook accounts with the same sense of obligation one might have toward publishing a fax number, and they started warning people not to stick their fingers into light sockets because they thought this was “content marketing.”

The first group are the ones who realize they were getting some of the best advertising available for free, while the second group is buying Twitter followers and not really getting the point.

I guess, in summary, I would say:

The adoption of an information professional is about being able to remain competitive with regard to how an organization levers its content.

And there it is—the tweet I was looking for.

Thank you for this series, Deb. You have, indeed, answered the call. :)

David Diamond

Picturepark

David, thank you for tirelessly advocating on behalf of information professionals in DAM. And thanks Ralph for giving my thoughts a place to live in the DAMosphere. It’s an exciting time to be an information professional for sure!

It seems I had a lot to say on this subject! I considered adding a summary, or “10 reasons to hire an Info Pro Right Now” at the end, but then this piece would have been even longer. Perhaps an executive summary (I feel an infographic coming on) would more easily find its way into the right hands in this age of too little time and too short attention span… ;-)

Looking forward to more DAM conversations,

-The DAM Librarian

Very nice!

Brilliant Article with in-depth information.