Who Needs a DAM Librarian? Part III: An Open Cover Letter

This is the third part of Deborah Fanslow’s article series: Who Needs a DAM Librarian? Part two is also available for anyone who has not read it. Deborah is one of the editors of The DAM Directory and an MLIS qualified librarian. A PDF copy of this article can also be downloaded.

So now that information professionals have been thoroughly cataloged and classified in relation to the field of DAM and the family of information management disciplines, it’s time to turn our attention to the skills and experience that information professionals bring to the DAM table. But wait—how can a newbie in the field possibly know how particular skills can or cannot translate over to a field of which she is not yet intimately acquainted? That’s a good question, and you are right to ask it.

As an aspiring digital asset manager myself, I cannot (yet) claim significant hands-on experience with enterprise level DAM implementations specific to the private sector. To date, most of my DAM experience has been acquired within the education and cultural heritage sectors—although I count my years as an early DAM user as the most valuable DAM education I could possibly receive. As a Random House alumna, I can only look back now and chuckle as I imagine the change management discussions that must have taken place during their enterprise DAM implementation, trying to get “those artsy types” to go along with new (and complex) file naming schemes, folder structures, digital templates, and production workflows just so some files could be tossed into the “SMART archive” (a.k.a, Artesia, circa. early 2000s), only to come out again as flat printer files. Those were the days!

As someone who worked in the creative trenches both as a DAM user and as the DAM itself, left the field to acquire an LIS degree with “extras,” then returned to work within various LAM-DAM positions, I can however offer a broad perspective on how the skills of information professionals stack up against the available criteria proposed for DAM work. This is not unlike what savvy job seekers aim to do when tailoring their cover letters towards a job and organization for which they have only limited information. So in answer to David’s call for us to come out of the library closet and boldly market ourselves, consider the last half of this series as an open cover letter to hiring managers—both those who may sit behind a vendor’s desk or are tasked with sourcing some DAM talent in some capacity.

In keeping with the theme of DAM and digital curation/stewardship existing as parallel fields (with more in common than not) as discussed in the previous article, the focus of the remaining articles in this series will be on presenting the case for the relevancy and transferability of information professionals’ skills across industry sectors. I will answer David’s call, making the case using my personal experiences, along with wisdom gleaned from studying with and being mentored by many DAM industry leaders who have been so unbelievably generous with their time and willingness to share their passion with aspiring DAM professionals like me. Along the way, I will weave in some more objective measures that will illustrate how the skill sets of information professionals (and by association, the LIS degree) compare to the skills needed to be a successful digital asset manager within the DAM field.

So, let’s get started, shall we? Wait, not so fast. First, we need a benchmark.

The DAM Skills Map

So what skills are required to be a competent digital asset manager these days? Thankfully, the most sage denizens of the DAM community—DAM consultants, that is—have generously shared their insight on what it takes to succeed in DAM:

Responding to a high volume of reader questions on this topic, Henrik de Gyor shared his criteria:

- What Does a Digital Asset Manager Need to Know?

- What specific skills should Digital Asset Management professionals have today?

- What are the levels of DAM experience?

In her analysis of the 2012 DAM Foundation salary survey, Elizabeth Keathley noted that DAM work requires highly specialized content knowledge and is comparable to the work of:

- System administrators

- Librarians

- Educators

- Archivists/records managers

- Project managers (Keathley, 2013).

The DAM Foundation’s human resources committee has also put together some detailed job description templates that outline the roles, key qualifications, and responsibilities for DAM professionals at a variety of levels:

- Digital Asset Management Specialist

- Digital Asset Manager

- Digital Asset Manager Director/Vice President

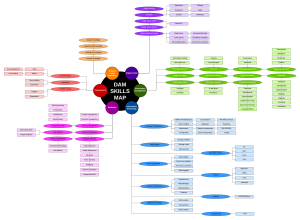

Now, quick quiz…what do you get when you combine graphic design and library science? Information design, of course! So, let’s see what happens when we classify these skills (inclusive of all administrative levels) by discipline—keeping in mind of course that the structure of any taxonomy represents only one of many possible perspectives:

(clik to open high-res edition)

Okay, so the DAM Skills Map is not exactly a standards compliant taxonomy…I cheated a bit by “up-posting” some terms for economy of display, and I didn’t go all out and indicate polyhierarchies — of which there would be many, considering the heavy overlap between information management and information technology skills. It would also be an interesting exercise to arrange the terms along the DAM Maturity Model dimensions of People, Processes, Information, and Technology—but that’s a different article. Regardless of how you arrange the skills, it’s easy to see why most DAM jobs are not entry-level positions!

The breadth and depth of skills required to be a successful digital asset manager indicate the need for more “DAM Whisperers”—professionals who can adeptly wield the strings of this multidisciplinary DAM marionette, leveraging their mastery of any number of these skills in combination when needed.

Supply and demand

Within last year’s post-Henry Stewart conference “State of the DAM Address,” David Lipsey remarked on the demand for professionals with competencies in digital asset management:

“Like the relentless force of gravity, all business data and promotional material are pulled towards a digital format. This has been dubbed ‘LED’ (Leading Everything Digital). As the force of LED increases, the importance of DAM throughout the worlds of industry, commerce, leisure, not-for-profit and government grows. The consequence: DAM professionals and DAM expertise are increasingly in demand and career opportunities expand.

DAM is now all pervasive; relevant to every aspect of our lives. Omni-channel marketing is an assumed basic necessity. Of course this means the spotlight is on smart content and intelligent metadata. In short: DAM competence is of fundamental importance [emphasis added].”

Not only is demand high for this skill set, but as Ian Matzen recently noted, “Employers are currently contending with an experience gap: there are fewer skilled and experienced DAM candidates than can meet the demand” (Matzen, para. 10). So how can the supply of DAM Whisperers be augmented to meet this growing demand? One way is to support the education and development of in-house professionals who have specific industry experience but are lacking DAM subject expertise. After that well runs dry, it becomes time to take the opposite approach. Strategic poaching of external subject matter experts should be undertaken, with education and development provided to support the acquisition of specific industry experience. I’m sure readers know where this argument is headed…

Both of these tactics require education. Until recently, there were two likely avenues to a career in DAM—on the job learning (a.k.a. the “baptism by fire” approach), and formal education, which has increasingly come to mean…the Library and Information Science (LIS) degree.

The “accidental” DAM professional

Early on, the path to a career in DAM was largely organic. Because DAM developed first within content-driven organizations, content creators (a.k.a. “creatives:” photographers, graphic designers, video editors, and other media professionals) often got bitten by the DAM bug through exposure (willingly or not!) during their early career experiences. Baptized by fire, as they say, these brave pioneers learned information management and technology skills on the job through mentoring, professional development, and dialogue with others in the same predicament. These courageous souls earned themselves honorary information management degrees through experience—a.k.a., blood, sweat, and tears. If they didn’t run screaming from these new responsibilities, they officially crossed over the threshold to become content managers, or “accidental” DAM professionals, as I call them—a term that seems befitting, and used here affectionately in honor of the growing book series by that name.

All of these professionals successfully leveraged their creative skills (knowledge of digital media production, creative tools, creative/production workflows, licensing, etc.) in addition to their newfound information management and technology skills to become highly competent digital asset managers who understood both creative users’ needs and information systems—a potent formula for success.

The “intentional” DAM professional

In 2009, Henrik de Gyor described the varied career backgrounds of people working in DAM at the time. His list included professionals from business, creative, communications, and information management fields. Not surprisingly, many of these fields align closely with the disciplines outlined in the DAM Skills Map.

While a variety of professionals continued to gravitate into the DAM field, some of the accidental DAM professionals (the ones with secret OCD tendencies?) sought treatment for their organizational proclivities, subsequently pursuing formal education in library and information sciences to become some of the first “intentional” DAM professionals. Some even lived to tell about it—with varying levels of enthusiasm about their particular LIS programs:

- FAQ – My Thoughts on MLIS and MY Background (Leala Abbott, 2009)

- Another DAM podcast interview with Michael Hollitscher (Michael Hollitscher, 2010)

- Tracy Guza: About (Tracy Guza, n.d.)

- DAM: A Career Opportunity for Info Pros (Kiersten Bryant, 2014)

- Reflections of a First-Year DAM Professional (Ian Matzen, 2015)

The LIS degree

Because managing digital assets is a critical need within every industry, subject matter expertise from any field can be leveraged towards a career in DAM. However, like it or not, as long as DAM work involves selecting, describing, managing, preserving, and distributing a collection of data, the acquisition of specialized information management skills will always stand as one of the critical prerequisites for DAM success. And one of the ways to acquire these skills is by earning a LIS degree.

As it turns out, information professionals are increasingly receiving education and training in more than just information management skills. As discussed in the previous article, LIS departments are continually adapting their curricula in an effort to match skills needed in the workforce (of course, the rate of curriculum alignment and development varies widely—buyer beware!), with increasing recognition of skills specific to digital asset management within the private sector.

One only has to post about DAM education opportunities within higher education on popular social networks to incite vehement debate on the value of an academic degree these days. However contentious the issue of the “academic machine” may be, the LIS degree is increasingly listed as a desired qualification on DAM job advertisements—and some employers consider it mandatory, as Tony Gill explained in his 2011 Another DAM Podcast interview:

“From my part, if you want to come work on my team, you will need a Library Science degree. That’s a graduate degree in Library and Information Science. That’s a really good grounding in the kind of disciplines that are very good in the Digital Assets Management field….It teaches you the importance of information architecture and information management. It teaches you to be rigorous and to follow standards. It also teaches you an observance for finickiness and attention to detail” (transcript, [4:33]).

So the LIS degree is proving itself to be a strong foundation for DAM work, as well as an increasingly valuable credential for aspiring DAM professionals to possess. Perhaps it’s time we took a closer look at LIS education (focusing on the U.S., since that is my experience base), and what LIS graduates have to offer in the way of transferable DAM skills. To see what skills information professionals bring to the DAM table, let’s imagine being a “fly on the wall” during an interview between an information professional and a hiring manager:

Interview with an Info Pro

[Act 1, Scene 1]

Hiring Manager: “So, tell me about yourself…”

Info Pro: Information professionals come from all walks of life. Because a secondary degree is required to become an information professional in most countries, many who have earned their stripes do so after working in a different field. Like educators and other cross-disciplinary professionals, information professionals often gravitate towards library and information science careers because they can’t imagine reigning in their curiosity and restricting their passion for learning to just one subject. Or, perhaps they sensed that their feelings of bliss when walking into a well organized stationery store and their overwhelming urges to reorganize grocery store displays were not shared by most of the population, and that they would do well to find a healthy outlet to satisfy their marginally acceptable impulses?

See also: Information Professionals: A Field Guide

Hiring Manager: “What are your qualifications?”

Info Pro: The vast majority of LIS degrees are offered as graduate programs of study. Some common abbreviations a hiring manager might see proudly displayed on a resume are the MLS, MLIS, MSLIS, MSLS, MARA, and even the MADAM! Traditionally, library/information science programs and archival studies programs were offered separately. Today, many institutions offer combined programs as well.

What does this mean for the hiring manager? In short, these abbreviations don’t tell you much at a glance. LIS students can take vastly different coursework that may or may not align closely with DAM work, and still add the same letters to their name after graduation. Like with any profession, the name of a degree does not matter so much as the knowledge and skills obtained throughout the process. So how does a hiring manager know if a particular candidate has obtained the transferable knowledge, skills, and experience that would enable him or her to become a DAM Whisperer? Or, on the flip side, how can aspiring DAM professionals tailor their coursework to prepare for a DAM career? Now that DAM professionals have offered their two cents on what it takes, their advice along with the handy DAM Skills Map can be used as a tool for comparison.

Today’s LIS students typically take a core set of required coursework that covers the foundational topics of human information behavior and information organization, resources, and services. Elective courses are commonly organized along prescribed “tracks,” “concentrations,” or “pathways.” These designations may or may not be listed on the actual degree; they are often used for advisory purposes to help students choose electives that are geared toward specific careers. These tracks, such as digital services, archives management, academic librarianship, digital curation, information architecture, etc., are also frequently bundled into Post-Master’s certificate programs for LIS graduates who want to update their skill sets.

Hiring Manager: “What skills can you bring to this role?”

Info Pro: While readers may still be working their way through the advocacy timeline from the first article, it is worth highlighting again one example in particular. In 2012, Deb Hunt shared a list of skills that librarians bring to DAM based on her own experience working in the DAM field:

- An understanding of audiences: who they are, what they look for and how.

- Expertise in building metadata schemas and taxonomies.

- Recognising the business value that finding information brings to an organisation.

- Experience creating IP policies that address copyright issues.

- Experience and expertise organising assets of all kinds and knowing that you get out of

a record what you put into it. - Knowing how to organise information and assets for findability.

- Generally they are viewed as neutral, working for the good of the entire organisation.

- Having a big picture view

- Can contribute to workflow strategies

- Able to prioritise what needs to be indexed first and why.

- Knowing to start small and let the success of a DAM project speak for itself. (Hunt, 2012)

Hiring Manager: “Can you expand on that?”

Info Pro: I will build on Deb’s list with more details on the various information management principles and practices that LIS students have the opportunity to learn these days:

Users are from Mars, IR systems are from Venus…

Information retrieval (search) will always involve the challenge of interfacing between an information retrieval system (often a database such as a DAM or CMS system) and the user, who communicate using quite different languages. The more one understands the intermediary language used, the better one is able to formulate an effective search strategy in order to find relevant and pertinent information.

- Information behavior (I’ll know it when I see it…)

Nearly every LIS student’s journey begins with understanding the information seeking process. To make a long story short:

- Searching is a complex, dynamic process; users don’t always know what they are looking for; and what we find changes what we seek.

- Moore’s Law as applied to Zipf’s Principle of Least Effort illustrates the need for balancing system complexity with functionality as presented through the user interface.

- Information retrieval (IR) systems (why can’t this DAM thing just work like Google?)

LIS students learn to design, query, and evaluate information retrieval systems, as well as:

- Methods for representing, storing, and accessing data.

- The sweet simplicity and efficiency of inverted files.

- The truth of garbage in, garbage out—that the ability to retrieve data is directly related to how that data is indexed. In fact, if it’s not in the index, it may as well not exist.

- The fundamental value of classification in enabling data exchange.

- IR system evaluation: the many ways to measure relevance, factors that affect recall and precision, and the strengths/weaknesses of different types of search systems.

- The effect of various data structures (free text, picklists, multi-value fields, hierarchical data, etc.) on indexing and retrieval capabilities.

“The more we get together, the happier we’ll be…”—a healthy codependence

LIS students learn how to structure data using knowledge organization systems—in effect, creating an intermediary language that can be used to enable communication between a user and the system. It is the value of this knowledge to which David Diamond alludes when he sells the value of information professionals’ ability to configure DAM systems properly.

A DAM system is fundamentally a highly specialized information retrieval system, which, in order to be useful within a specific business context, requires the creation of a custom intermediary “language” based on specific business rules. Throughout their coursework and internships, LIS students receive abundant training in interfacing between the language of users and systems to make information findable. They learn the art and science of using data models (metadata schemas) and structured languages (controlled vocabularies) to embed or link information to assets (a.k.a. cataloging/indexing), enabling them to be searched and retrieved effectively from within an information system.

- Cataloging (love it or hate it, we can’t completely automate it…yet)

Cataloging is not to be confused with basic data entry, and is not for the faint of heart. It involves:

- Authority control: getting your preferred terms in alignment.

- Subject analysis: “aboutness,” and the attempt to make the subjective more objective.

- Classification: realizing that in the digital world, entities can live in more than one place.

- Representing information in a record using standards and rules.

- Describing and classifying assets with an understanding of users’ information needs and the effect of indexing on search effectiveness.

- Metadata (don’t leave home without it!)

LIS students learn that metadata is absolutely critical for the identification, organization, exchange, and preservation of data—and that if you want to share your data, you need to structure it, standardize it, encode it, and document it. This involves:

- Metadata schemas—why there will never be just one.

- Standards (details, details…)

- Data structures: what fields are used and what they mean.

- Value encoding schemes: what terms are used within the data fields.

- Data content standards: how to format the terms used within the fields.

- Encoding formats: the syntax used to encode the data for machine processing (HTML, XML, RDF, etc.).

- Interoperability and other important principles (it’s always nice to share…)

- Mapping/crosswalking (handy for those data migration projects)

- Harvesting (machine aggregation)

- Federated searching

- Interoperability protocols

- Repositories/registries

- Documentation (data dictionaries, application profiles)

- Controlled vocabularies (it always comes down to control, doesn’t it?)

Controlled vocabularies (taxonomies, thesauri, ontologies, etc.) are all the rage these days. LIS students learn how to leverage the power of vocabularies to map terms and their relationships to a unified business language that enables users to translate their information needs into effective searches. They learn:

- When, where, and how to use different types of controlled vocabularies (synonym rings, authority files, taxonomies, thesauri, ontologies…or perhaps a hybrid?).

- How controlled vocabularies are increasingly being used to describe and link data on

the web.

- Search (it’s gotta be in here somewhere…)

Search is where the rubber hits the road. LIS students learn how metadata and controlled vocabularies power effective search. They learn:

- The basics: the types of information retrieval models; how, when, and why to use various search techniques (keyword, Boolean, etc.); and how to adapt a search strategy to match depth of indexing.

- Truth #1: findability is a function of how information is stored in an IR system, how an IR system interacts with the information, and the searcher’s knowledge.

- Truth #2: effective information retrieval depends on how well an IR system can aggregate and discriminate data based on its attributes, which are captured as metadata. If you don’t add metadata to your assets, then you won’t be able to find them.

- Truth #3: controlled vocabularies should be integrated with search by linking taxonomy terms to data records, and leveraging them in the user interface (folder browsing, breadcrumbs, predictive search, related assets, etc.).

- Truth #4: if you don’t have a field to hold and link your controlled vocabulary to your assets, then your vocabulary is useless.

“Tables and rows, and objects and nodes…that’s what databases are made of”

Of course, budding information professionals need to learn how to search databases like the backs of their hands. However, they also move past the sugar and spice and go deep under the hood:

- Database systems (so many databases, so little time…)

LIS students receive a crash course in using many types of databases:

- Bibliographic databases: online catalogs of surrogate records, integrated with modules for cataloging, circulation, inventory, etc.

- Citation databases: databases of surrogate records that contain content indexed in yet another database.

- Full text databases: highly specialized databases that often employ complex controlled vocabularies.

- Multimedia databases: digital library systems, “trusted” digital repositories,

DAM systems, etc.

- Database design/management (entities, attributes, and relationships—oh my!)

So where does all that metadata actually go? The basics of creating databases (predominantly RDBMS) is considered foundational:

- Data modeling: ERDs, schemas, normalization, etc.

- Data implementation/querying: creating SQL commands and queries.

- Data access: creating web-based access to dynamic data.

- Programming (commanding those 0s and 1s)

Increasingly, courses are popping up on basic programming that cover:

- Data representations, structures, and syntax.

- Problem solving, debugging, and resolving happy coding accidents.

- Networking (not just vital for your career, but also for data transfer!)

Although LIS students likely won’t be tinkering with their schools’ servers, they can learn about

the principles of:

- Local area network (LAN) hardware, topologies, operating systems, and applications.

- Network protocols and distributed systems.

- Database configuration (gatekeeping)

At some point (typically in an internship), LIS students will learn the basics of configuring database systems:

- Account management: creating users and groups.

- Data security: setting roles and permissions.

- Statistics: creating and analyzing system, user, and asset reports.

It’s what’s on the outside that counts after all

In addition to learning what goes on behind the scenes, LIS students learn the basics of presenting and organizing information on the front end.

- Web design (you put your left tag here, you put your right tag here…and script it all about)

How to structure, store, process, access, and present information on the Web has become an essential skill, which involves learning:

- Web coding: HTML, CSS, etc.

- Client and server side scripting: Javascript, PHP, etc.

- Interface design: designing for usability and accessibility.

- User Experience (UX) (digital wayfinding)

LIS students learn to use and evaluate an array of user interfaces, which provides a strong foundation in knowing what works and what doesn’t when searching for information! They learn:

- Information architecture: navigation, labeling, search, etc.

- Interaction design: easier said than done.

- Information visualization: how to visually represent data effectively.

- User centered design: the value of user research and continuous usability testing.

“Let’s get digital, digital…”

After learning the basic principles of information organization, LIS students learn the unique challenges of managing digital assets.

- Digitization (what’s old is new again!)

Digitization projects provide excellent opportunities for LIS students to put all of the above principles to work, which commonly involves:

- Selection/Appraisal: prioritizing assets for digitization.

- Technical standards: file formats, naming conventions, codecs, and more.

- Digital imaging: the intricacies of photography and color management.

- Media editing: how to capture high quality master assets.

- Copyright/licensing: the complexities of determining copyright status.

- Digital curation/stewardship/asset management (hands down, DAM wins for best acronym)

The active management of assets throughout their lifecycle requires more than just technology. LIS students learn about the value of policies, workflows, and documentation! They learn:

- That the entire lifecycle of digital assets must be taken into account.

- Principles and best practices in the selection/appraisal, acquisition, arrangement, description, storage, migration, retention, and preservation of digital assets.

- How to plan for sufficient access and reuse of digital assets.

- Digital rights management (every rose has its thorn)

An understanding of the complex issues and ever changing legal implications of intellectual property rights is fundamental to LIS education, including topics such as:

- Copyright and fair use, licensing and contracts, and vendor negotiation.

- The implications of ownership of vs. access to information.

- Digital preservation (planning ahead despite not having a crystal ball)

LIS students learn about the unique management, technology, and content issues involved in preserving digital data, including:

- The need to preserve more than just a digital file.

- The importance of determining and maintaining the authenticity of data.

- Digital preservation strategies and standards.

- The importance of data storage architecture.

- How to recover data using forensic technologies.

Sometimes, relationships require professional help

LIS students discover that helping users learn how to use an IR system to find what they need involves ongoing education, support, and encouragement.

- Instruction (learn some algebra and get in shape at the same time with Boolean aerobics!)

In person and virtual instruction is part and parcel of LIS education. LIS students do not escape their degree program without providing instructional services in some capacity, including:

- How to teach: principles and practices based on learning theories (how people learn) and informed by assessments (did people learn what we wanted them to learn?).

- Who to teach: Strategies for large group, small group, and 1-on-1 instruction, as well as how to master the art of one-shot instruction.

- When to teach: teaching is most effective at the time of need. Instructional materials should be available 24/7, so you don’t have to be!

- Where to teach: instruction should be embedded where users are—unobtrusively in the IR system, as well as where users interact with the system (portals, social media, etc.)

- With what to teach: screencasting, screen sharing, IM, and other handy (and free) instructional tools enable more dynamic and interactive learning experiences.

- Reference—a.k.a., the Help Desk (are you hearing what I’m not saying?)

LIS students learn that the only stupid question is the one not asked, and that even the most outspoken critics of an IR system can become its biggest proponents when their needs are heard, respected, and considered.

- The reference interview: listening to users and determining what they really need, despite what they might say they are looking for is a good skill to master.

- When providing customer service, strong communication skills are imperative.

- Change management (who moved my shortcut?)

Often part of leadership and management courses, change management is a topic which can be learned in theory during school, but understood truly through experience. This includes:

- Bottom up strategies: working with staff to implement change; building teams, recruiting early adopters, and involving users in the process.

- Top down strategies: getting administrative buy-in and support.

- Understanding how various personalities react to change, and adapting one’s strategy accordingly.

Relationships definitely require ongoing maintenance

Managing information requires more than just installing an information system, configuring it once, and then setting it on autopilot—no matter how intuitive a product may appear to be. LIS students learn that because people, processes, information, and technology change, so too do information needs.

- Documentation (if you were to win the lottery and head to the tropics tomorrow…)

The value of writing things down is not just a smart practice in “duck and cover” environments— it is also a best practice for effective knowledge management. LIS students learn that it is wise to take the time to document:

- Policies: selection policies, copyright policies, workflow policies, digital preservation policies…helpful for planning, and often for covering your assets.

- Procedures: uncovering all sorts of tacit knowledge that can be standardized and formalized into automated workflows; also good for when coworkers unexpectedly

jump ship. - Decisions: application profiles, data dictionaries, cataloging guides, etc.—share them widely and keep them current!

- Information governance (it’s always good to set some guidelines…)

LIS students learn that the information lifecycle never ends, and that one person cannot manage an ocean of information alone. This requires:

- For end users: continuous training opportunities, tailored to specific needs.

- For power users: in-depth training, cataloging guides, etc.

- For stakeholders: demonstrating the need for and effect of information governance informed by systematic analysis of asset, user, and system metrics; user feedback;

and an understanding of organizational goals.

Is it too late for a pre-nup?

“There’s never enough time to plan ahead, but there’s always time to do it over again.”—an adage that can be mitigated by thorough planning.

- Strategic planning (seeing the forest *and* the trees)

The formation of plans and policies is a common exercise for LIS students. They learn about:

- The forest: defining a mission and vision.

- The trees: creating goals, objectives, and timelines.

- Needs assessment: surveys, interviews, and focus groups.

- Resource allocation: budgeting—not just for the bean counters!

- Evaluation: what will success look like, and how will we measure it?

- Project management (PM) (oops…was I supposed to do that?)

Although LIS students gain plenty of experience managing projects throughout their academic career, formal project management methodologies are increasingly making an appearance within the LIS curriculum, including:

- PM basics: the project lifecycle, project management techniques, and tools to help

make it all happen without a nervous breakdown. - Working within constraints: there’s never enough time, money, or staff.

- Risk management: how to identify and prepare for life’s inevitable little hiccups.

- Project evaluation: what will success look like, and how will we measure it?

**********

[BRIEF INTERMISSION]

Phew! Let’s take a break from the interview for a moment, and let our interviewer recover, shall we?

In comparing the topics and skills taught within LIS curricula against the DAM Skills Map, one can see

an incredibly strong overlap. LIS schools are increasingly offering courses that provide foundational knowledge and skills within the majority of subject areas that are required of DAM professionals, and are frequently providing assistance in acquiring internships that enable students to hone these skills within

real world contexts.

So what’s missing?

- Context: the majority of LIS schools still focus on the application of digital asset management skills within the cultural heritage sector, despite the fact that these transferable skills are in high demand outside the traditional turf of libraries, archives, and museums. Increased exposure to the principles and methodologies of DAM as practiced within the private sector is clearly needed.

- Industry knowledge: in general, LIS curricula frequently focus on providing discovery and access to information, as well as preserving data for future use. Topics of greater interest to private sector industries such as monetizing assets, streamlining marketing/creative/production workflows, and repurposing content, for example, naturally do not receive as much attention—despite the fact that many cultural heritage organizations have their own marketing and creative departments that could provide fertile grounds for the implementation and study of more commercially oriented use cases. Interestingly, museums in particular have been increasingly dipping their toes into the commercial DAM scene, likely due to the increasing interest in monetizing their assets. As LAM education continues to converge, perhaps more of these types of case studies will make their way into the LIS curriculum.

- Semantic technologies: there is a relative scarcity of dedicated courses on vocabulary design and linked data. Indexing has always been a well covered topic within the LIS curriculum, but creating, managing, and implementing controlled vocabularies such as taxonomies, thesauri, and ontologies doesn’t seem to warrant a dedicated course yet. Data curation courses are popping up left and right in response to the Big Data movement, but courses in RDF, SPARQL, and other semantic technologies are still not mainstream within LIS curricula. This is surprising in light of the fact that linking and leveraging data is such a hot topic within all industry sectors today, and even more puzzling due to the fact that academics are actively involved with Linked Data initiatives, and finding instructors to teach these types of courses would likely not be a challenge.

- Internships: more partnerships need to be developed with organizations engaged in DAM implementations and programs in order to enable LIS students to apply their DAM skills within the private sector. This is a win-win situation both for the students and for organizations in need of additional temporary staff with specialized knowledge. Organizations can “try before they buy” as they set interns to work (physically or virtually) wrangling metadata, creating taxonomies, documenting procedures, training users, and much more. Interns can develop their skills and obtain practical experience in managing informational challenges within diverse industries, and then leverage that knowledge base to the advantage of their future employers.

The rise of DAM education

Fortunately, to fill these educational gaps, a third avenue to a career in DAM is emerging. DAM education as practiced within the private sector is becoming increasingly more available (and affordable!) outside of academia. To quote Ian Matzen’s reflections one last time,

“There seems to be no formal path to a DAM career. DAM internship programs could help to address this. The DAM Foundation and books—such as this one by Elizabeth Keathley—have made great strides towards standardizing the qualifications for DAM professionals. As a result, paths are being forged” (para. 10).

The DAM Foundation Education Committee recently took a big step forward in paving the way by unleashing its first DAM Certification course. In a DAM Guru Program blog post, Elizabeth Keathley noted that more IT and marketing professionals are becoming interested in learning more about DAM. Looking again at the DAM skills map, this is not entirely surprising since the fields of IT and marketing are highly entwined with DAM work. As the DAM community continues to grow, professionals with diverse education, skills, and experience will surely enrich the collective knowledge base.

And last year, the School of Information at San José State University (home of John Horodyski’s popular DAM course) opened their LIS courses to the general community. This is good news for aspiring DAM professionals who can now take online DAM-related courses (space permitting) without having to commit to a graduate degree program.

For those who prefer more informal DAM education, opportunities for indulging in self-education abound. Many educational resources are listed within the DAM Directory, a collaborative project created in coordination with the DAM Foundation which aims to serve as a digital reference library of curated DAM resources—created by and for the multidisciplinary DAM community.

Increased access to DAM specific education will help reduce the educational barrier for entry into the DAM field—not only for information professionals who may lack experience in the private sector, but also for hiring managers who can appreciate the LIS skill set but who are looking for DAM Whisperers who can quickly close the educational gap and get up to speed on DAM within their industry sector.

Coming up!

In the next (and last) article in this series, I’ll present Act II of the interview. I will describe how the skills of information professionals can be applied in the real world to bring substantial value to an organization. I hope to convince readers that information professionals not only have the potential to be superb digital asset managers, but that they also have the potential to contribute significant additional value to an organization’s enterprise wide digital strategy.

Share this Article:

GREAT Article!!! SO informative!